Collection: Religious Art

In Japanese history, religion is less a matter of doctrinal allegiance than a harmonious constellation of practices, each offering a lens on the sacred.

Shinto is Japan’s indigenous animistic religious tradition, centered on the veneration of kami—spirits or forces residing in natural phenomena, ancestral lines, mountains, rivers, and mythic deities. It emphasizes seasonal rites, and a harmonious relationship with nature. Shinto does not demand exclusive belief, allowing it to coexist fluidly with other traditions.

Introduced from the Korean peninsula in the 6th century, Buddhism became a defining force in Japanese art, statecraft, and intellectual life. For over a millennium, the distinction between Shinto and Buddhism was not firm. Temples housed Shinto deities; shrines enshrined Buddhist icons. Kami were interpreted as local manifestations (suijaku) of universal Buddhas (honji).

Though not institutionalized in Japan as formal religions, Daoism and Confucianism strongly influenced Japanese thought, government, and aesthetics. Daoism contributed deities, Immortal sages, cranes, and turtles as symbols of long life, The cosmological animals, The Five Elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, water) and Yin–Yang cosmology. Daoist motifs permeate esoteric Buddhist art (particularly Shingon) and literati painting (sennin figures, hermit sages, mountain ascetics).

Confucianism shaped: bushido, the samurai code and its ethics of loyalty, hierarchy, filial piety, and was the basis of the Tokugawa administrative and educational systems. Confucian symbols—such as plum blossoms, bamboo, and pine (the “Three Friends of Winter”)—became common themes in decorative arts.

Japanese religious sculpture is among the most refined in the world. Due to this confluence of thought, traditional religious furnishings in Japan span both Shinto and Buddhist spheres, often with shared forms and borrowed iconography from Daoism and Confucianism.

-

Ancient Bugaku Mask, Ryo-o (Rangryo) The Dragon King

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥796,900 JPYRegular price -

Set 5 Antique Japanese Negoro Lacquer Bowls

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥103,600 JPYRegular price -

Auspicious Bats by Buddhist Nun ー大石 順教

Vendor:Oishi JunkyoRegular price ¥191,300 JPYRegular price -

Important Buddhist Nun Calligraphy Scroll ー大石 順教 “いろは”

Vendor:Oishi JunkyoSold out -

Chrysanthemum Painting by Buddhist Nun ー大石 順教 半折 “菊花”

Vendor:Oishi JunkyoSold out -

Incredible Mother of Pearl Inlay Suzuri Bako Lacquer Writing Box

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥462,200 JPYRegular price -

Edo p. Japanese Mizusashi, 1851 ー大綱 宗彦, 喜祐 "雲堂水指"

Vendor:Taiko SogenSold out -

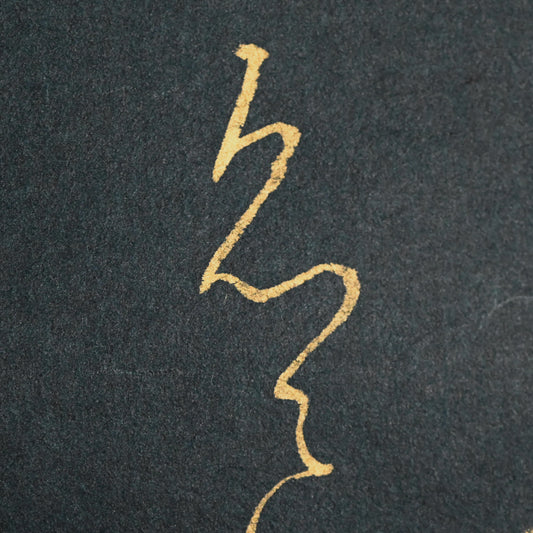

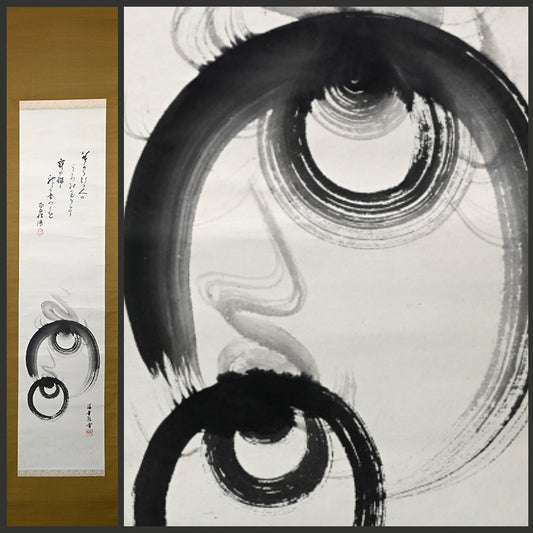

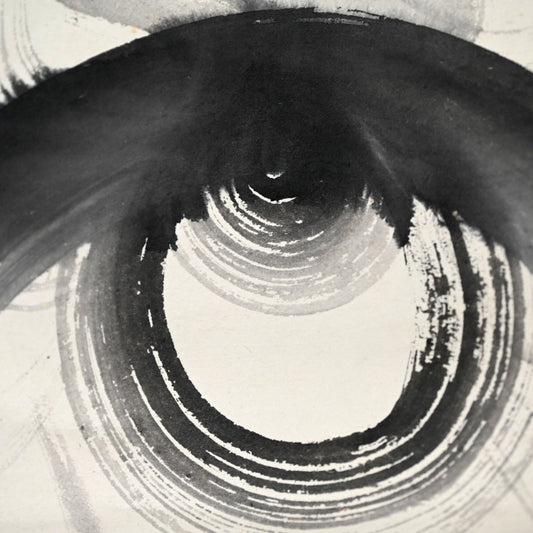

Mid-century Abstract Sumie Scroll ー大林 天洞

Vendor:Obayashi TendoSold out -

Meiji p. Zen Skull Painting ー尾竹 竹坡

Vendor:Otake ChikuhaRegular price ¥71,800 JPYRegular price -

Sold out

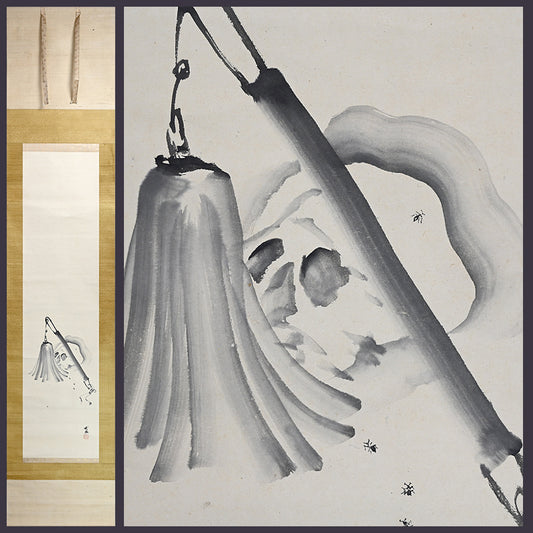

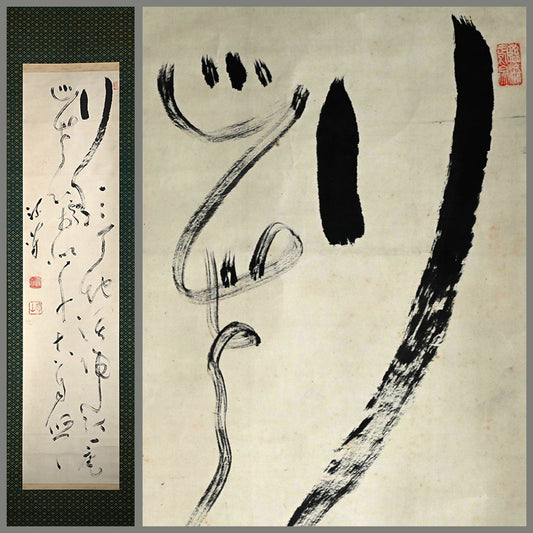

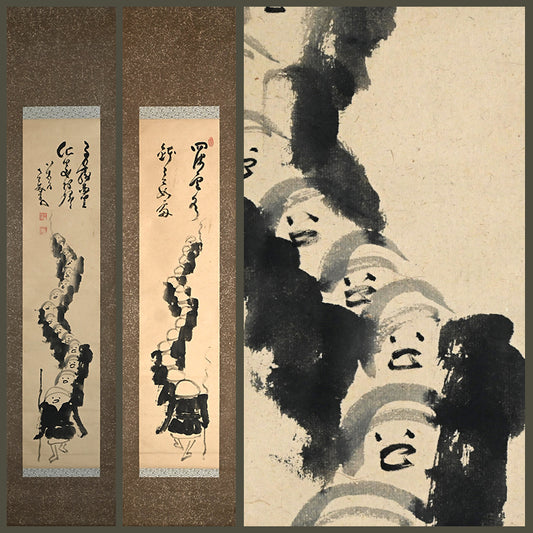

Sold outGathering Alms by Zen Priest ー中原 南天棒

Vendor:Nakahara NantenboSold out -

Antique Buddhist Image of the Zen Patriarch Daruma

Vendor:Kura Monzen GallerySold out -

Buddhist Image of a Burning Jewel ー小西 福年 "瑞宝圖"

Vendor:Konishi FukunenSold out -

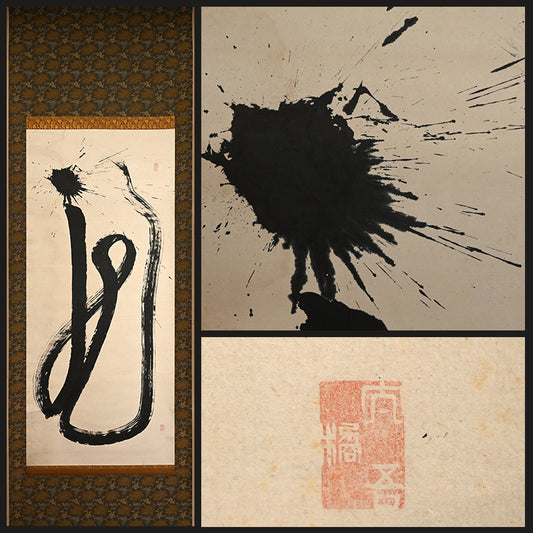

Calligraphy by Zen Priest, Antique Japanese Scroll ー橋本 独山 "二行書"

Vendor:Hashimoto DokuzanSold out -

Hakuzosu Fox in Priest Robes ー大田垣 蓮月 "白蔵主"

Vendor:Otagaki RengetsuSold out -

Antique Japanese Dragon Calligraphy Scroll

Vendor:Kura Monzen GallerySold out -

Goki, The Demon Attendant of En-no-Gyoja

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥796,900 JPYRegular price -

Ancient Wooden Tengu Mask, Kamakura to Muromachi period

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥796,900 JPYRegular price -

Pair of Edo period Inari Kitsune Fox Guardians

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥924,400 JPYRegular price -

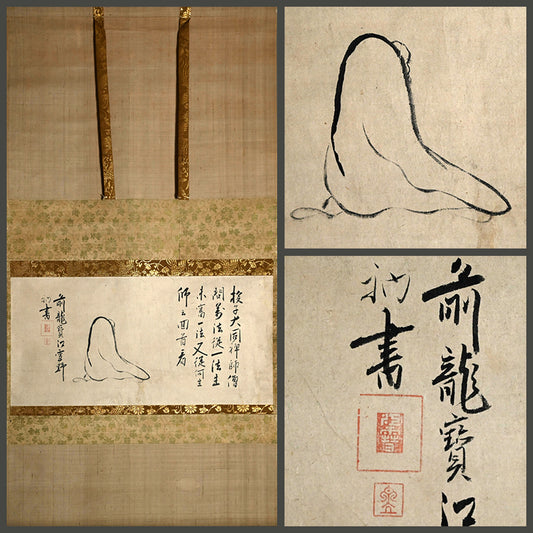

17th century Zenga Daruma Image by Priest ー江雪 宗立 “ダルマ”

Vendor:Kosetsu SoryuSold out -

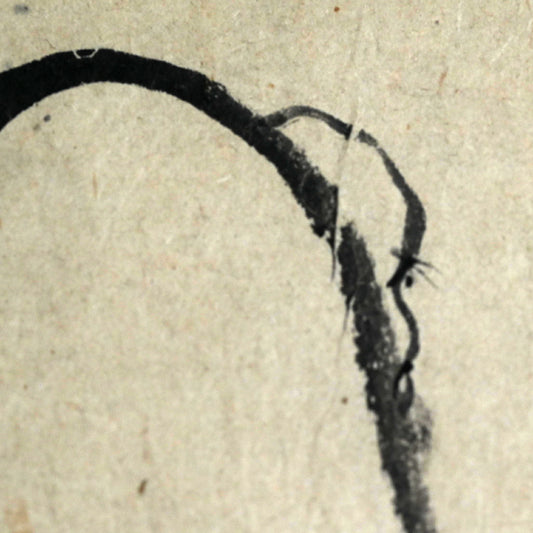

Edo p. Dragon Image by Priest ー如蓮 和尚 (大寅 和尚)

Vendor:Nyoren OshoSold out -

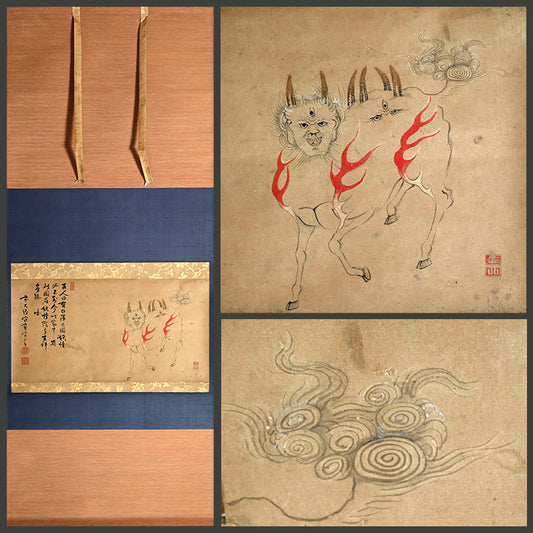

Edo p. Talismanic Scroll, Hakutaku by Zen Priest ー宙宝 宗宇 “白沢"

Vendor:Sou ChuhoRegular price ¥398,500 JPYRegular price -

Exquisite Vertical Kannon Triad

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥478,200 JPYRegular price -

Ancient Nyorai Kojin, Guardian Deity Scroll

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥717,200 JPYRegular price -

Rare Edo p. Japanese Buddhist Scroll, Daizuigu Bosatsu ー"大隨求菩薩尊像"

Vendor:Kura Monzen GallerySold out -

Buddhist Koro Incense Burner w/ Gilded Wooden Stand

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥103,600 JPYRegular price -

Gilded Sahari-do Buddhist Koro Incense Burner ー金砂張香炉

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥151,500 JPYRegular price