Collection: Samurai

The samurai, originally meaning “those who serve,” emerged in the late Heian period (794–1185) as provincial warrior bands employed by aristocratic landholders. By the Kamakura period “samurai” had ceased to describe simply hired swords; it denoted a hereditary warrior elite defined by martial skill, loyalty to a lord, and an emerging ethical and cultural identity. Although the historical samurai were not always paragons of virtue, the concept of Bushido— “the way of the warrior”—gradually emerged from Neo-Confucian ethics, Zen Buddhism, and medieval martial values. Honor, loyalty, frugality, and self-discipline became idealized characteristics, further elaborated in Edo-period teachings. Samurai became key patrons of arts and cultivated a literate, bureaucratic identity that helped shape early modern Japanese governance.

Kamon are hereditary family crests that developed alongside the samurai class. A family’s kamon was a visual expression of lineage, loyalty, and prestige. Initially armor, banners, and sashimono (back flags) displayed crests to distinguish allies from enemies amid the chaos of war. Later crests adorned kimono, lacquerware, armor, swords, and funeral equipment. By the Edo period, commoners—especially merchants and artisans—also adopted crests for branding, guild identity, and festival use.

The Meiji Restoration (1868), which restored imperial rule and sought rapid modernization, ended the samurai’s privileged position. Economic hardship and loss of status led to uprisings such as the Satsuma Rebellion (1877) led by Saigō Takamori, often seen as the final expression of samurai resistance to modernization. By the 1880s, the samurai class as a distinct social group had disappeared, though their cultural legacy persisted in military ideology, literature, and popular imagination.

-

Edo p. Japanese Bronze Koro Incense Burner, Samurai Armor

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥398,500 JPYRegular price -

Antique Japanese Sword Shaped Brush Case

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥286,900 JPYRegular price -

Incredible Mother of Pearl Inlay Suzuri Bako Lacquer Writing Box

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥462,200 JPYRegular price -

Antique Japanese Negoro Heishi Lacquered Vase Set

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥151,500 JPYRegular price -

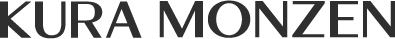

Iron Hanging Vase made of Yoroi (Samurai Armor) Parts

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥573,800 JPYRegular price -

Edo period Japanese Kiseto Chawan Tea Bowl ー黄瀬戸御茶碗

Vendor:Kura Monzen GallerySold out -

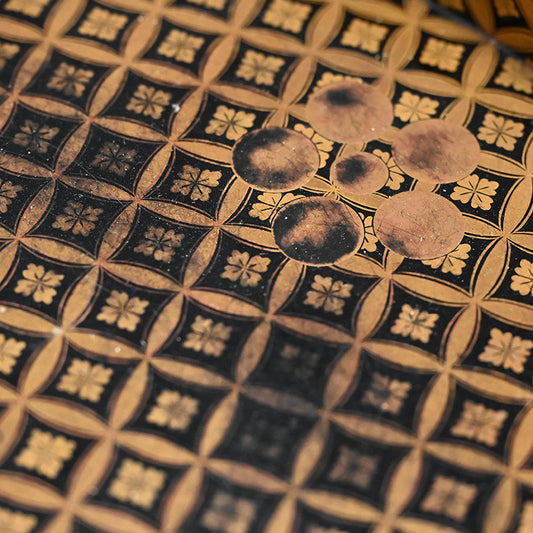

17th c. Tri-legged Antique Japanese Lacquer Tray with Gold Design ー時代蒔絵香盆

Vendor:Kura Monzen GalleryRegular price ¥143,500 JPYRegular price