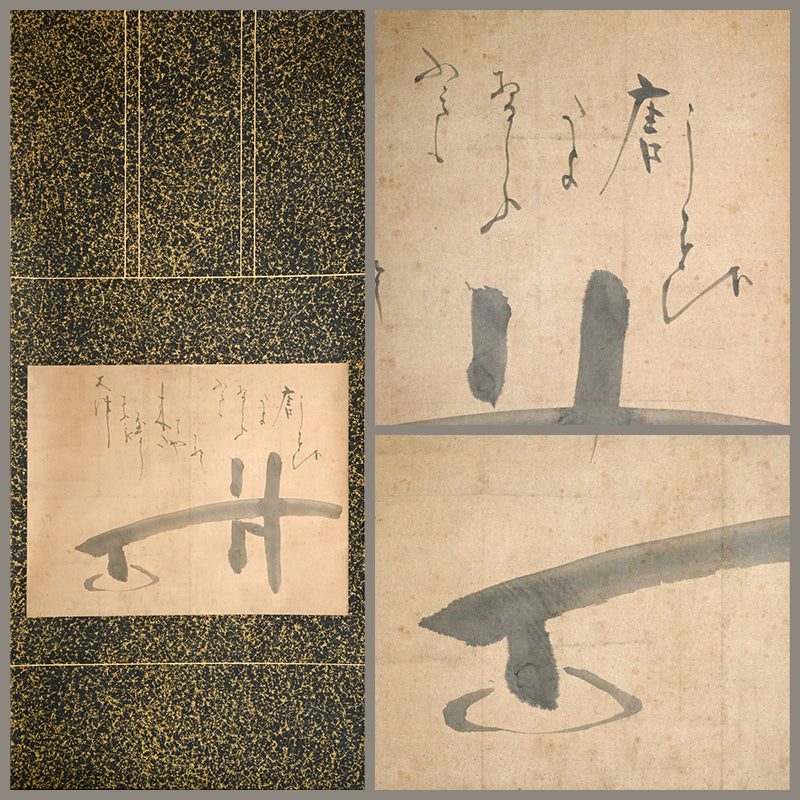

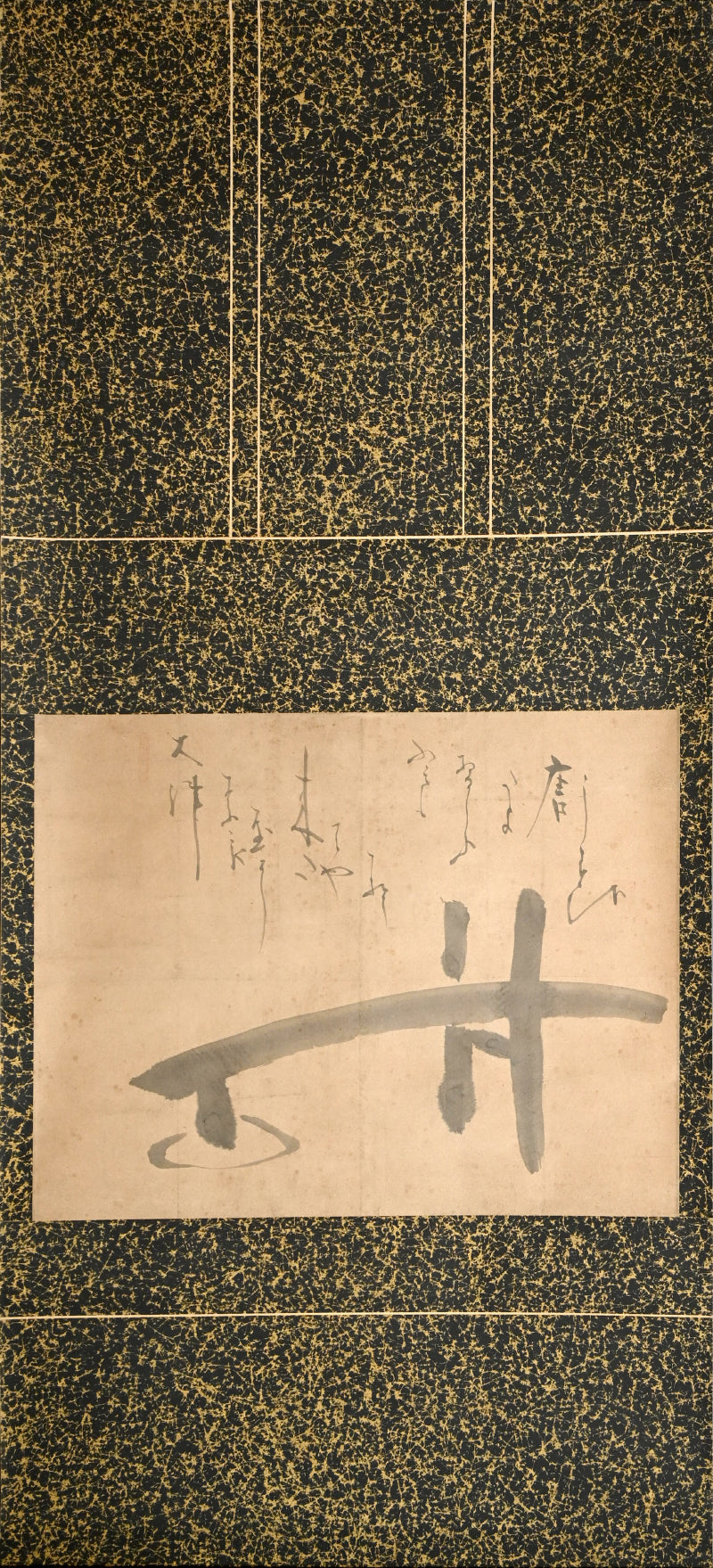

Mortar and Pestle by Hakuin Ekaku, Edo period Zen Painting ー白隠 慧鶴

Mortar and Pestle by Hakuin Ekaku, Edo period Zen Painting ー白隠 慧鶴

Item Code: Z027

Couldn't load pickup availability

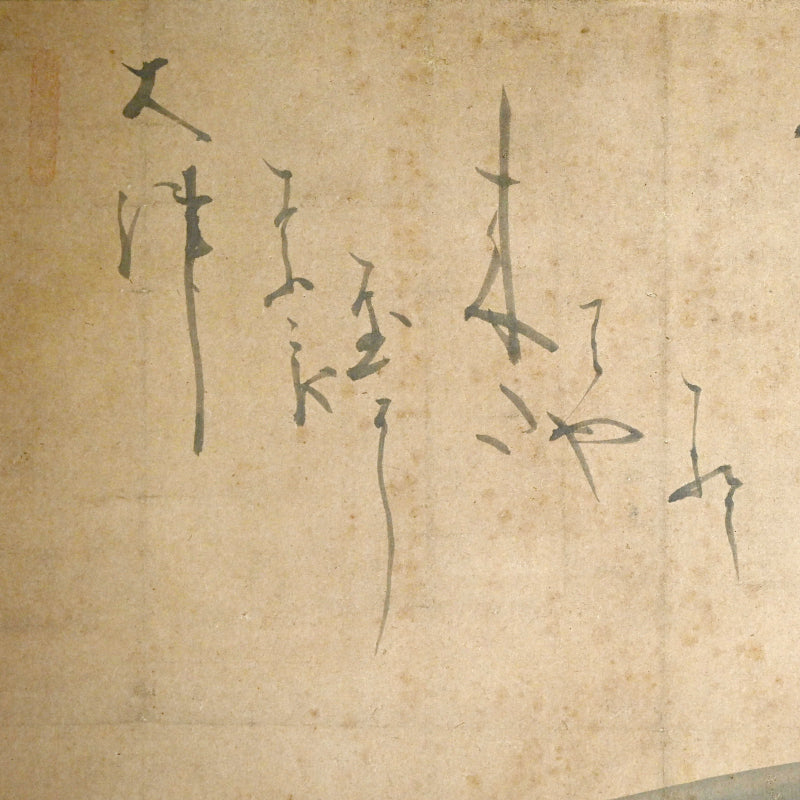

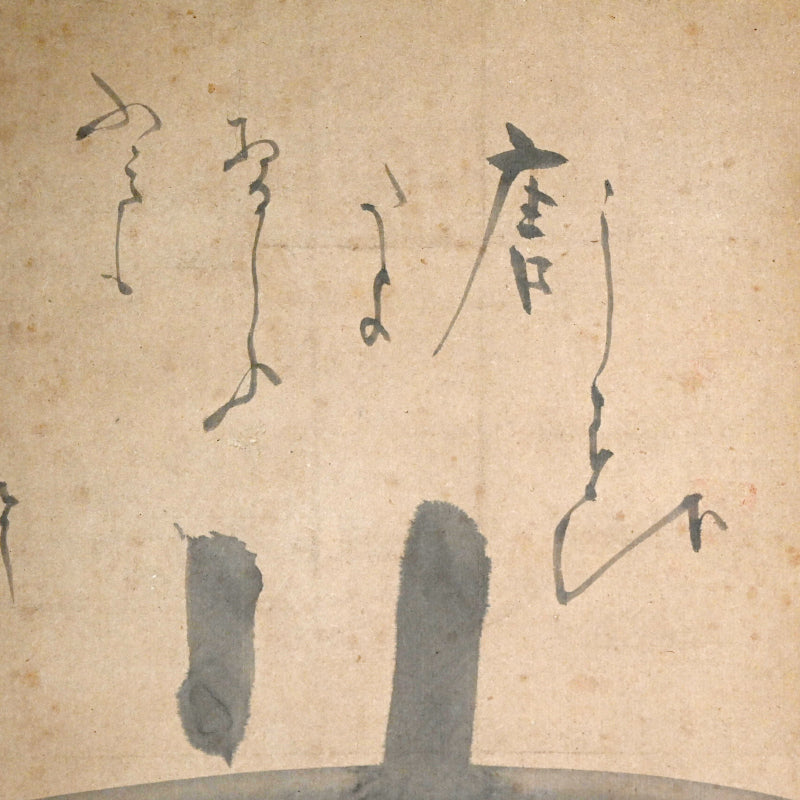

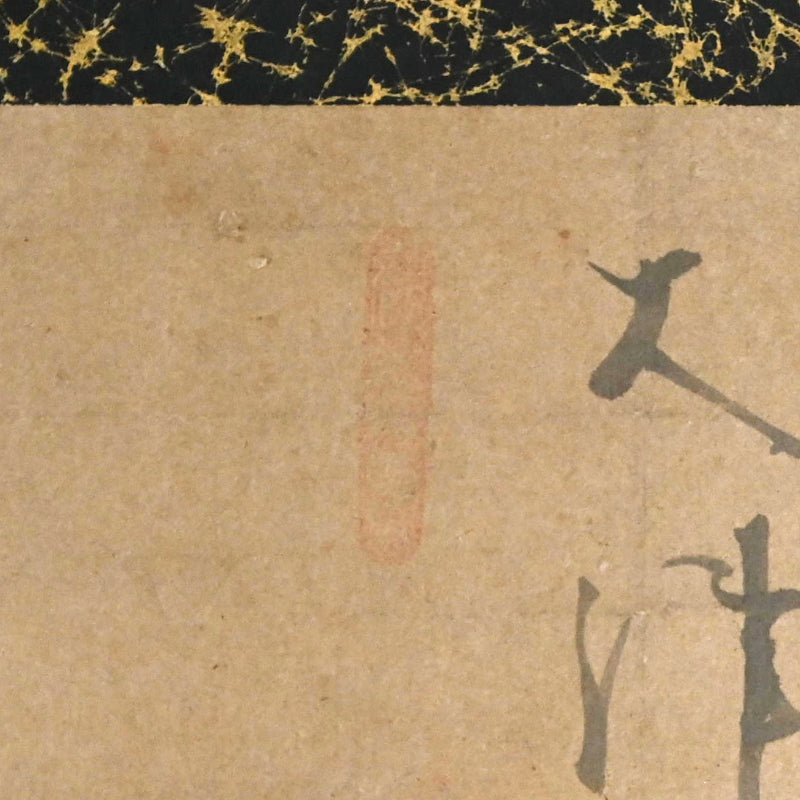

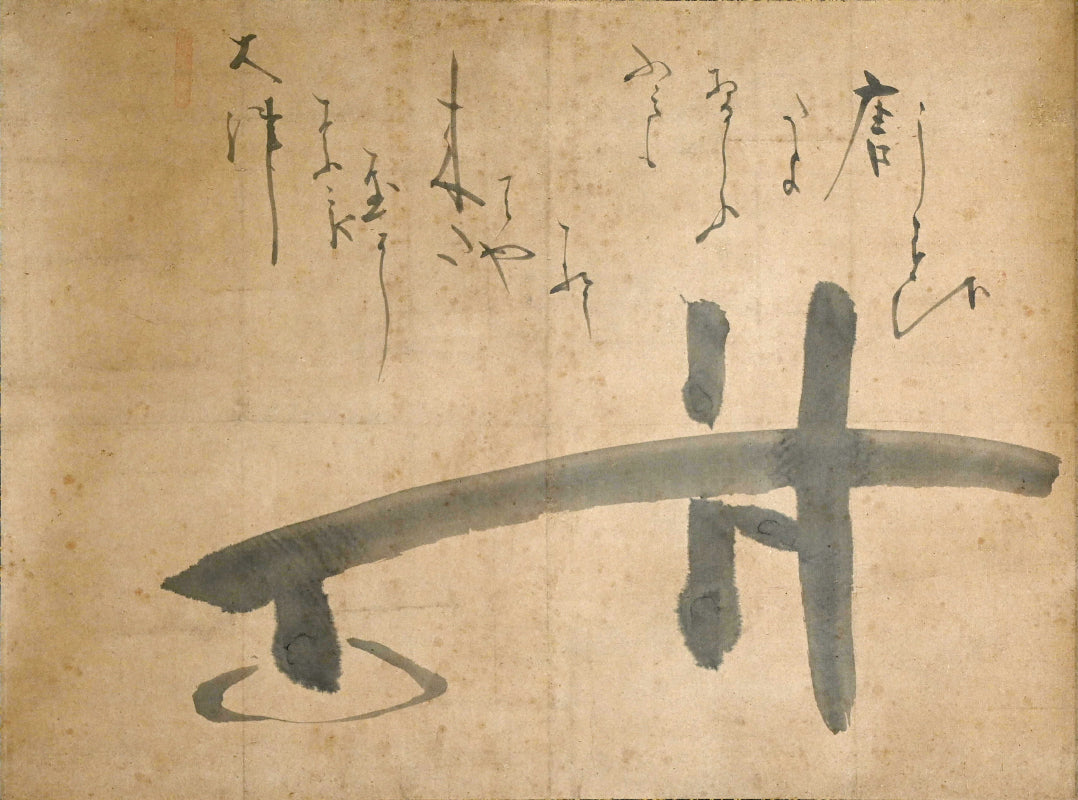

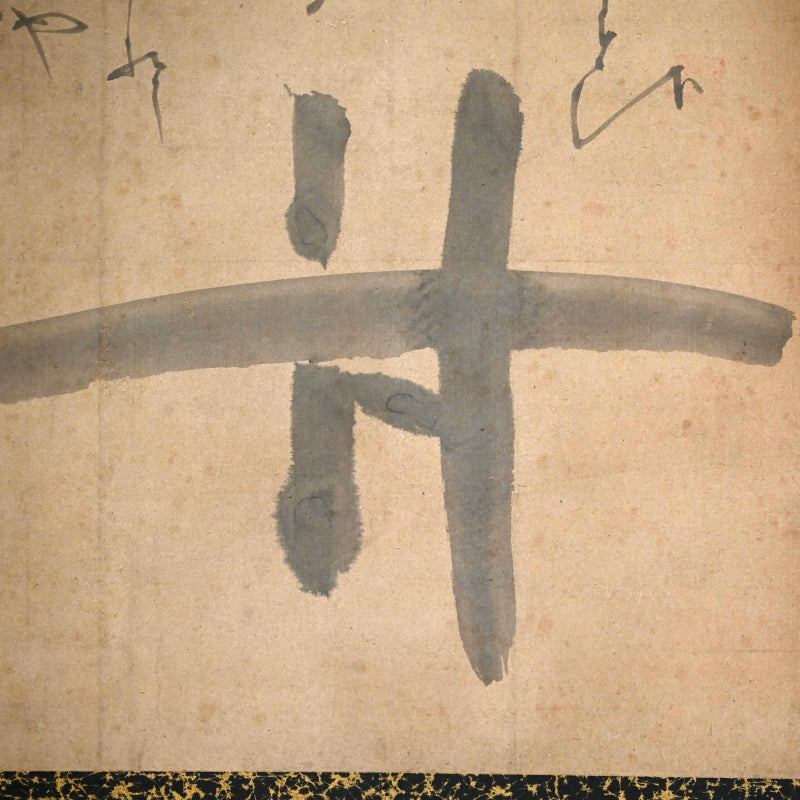

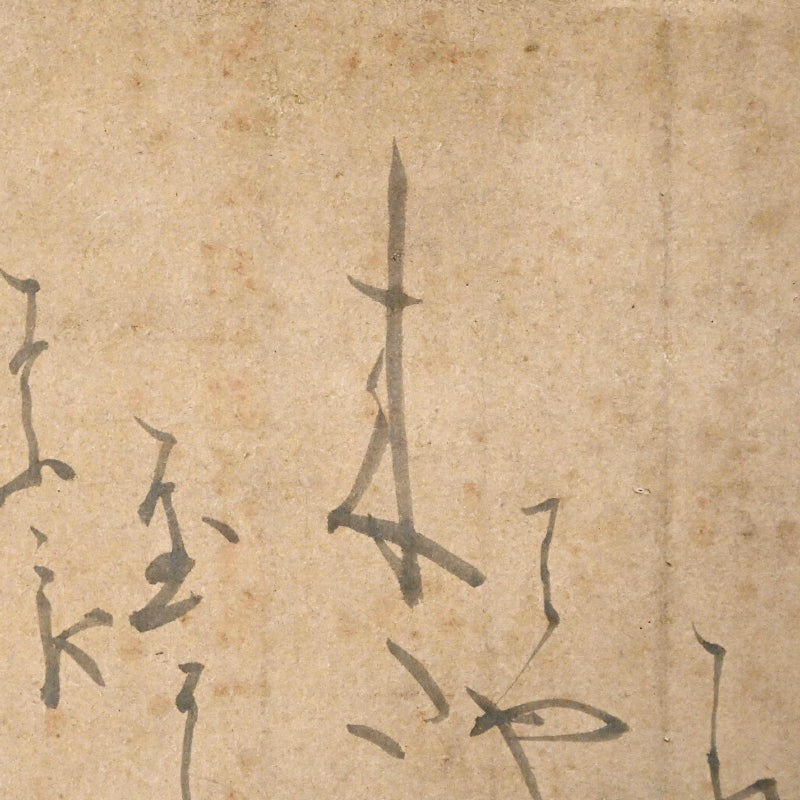

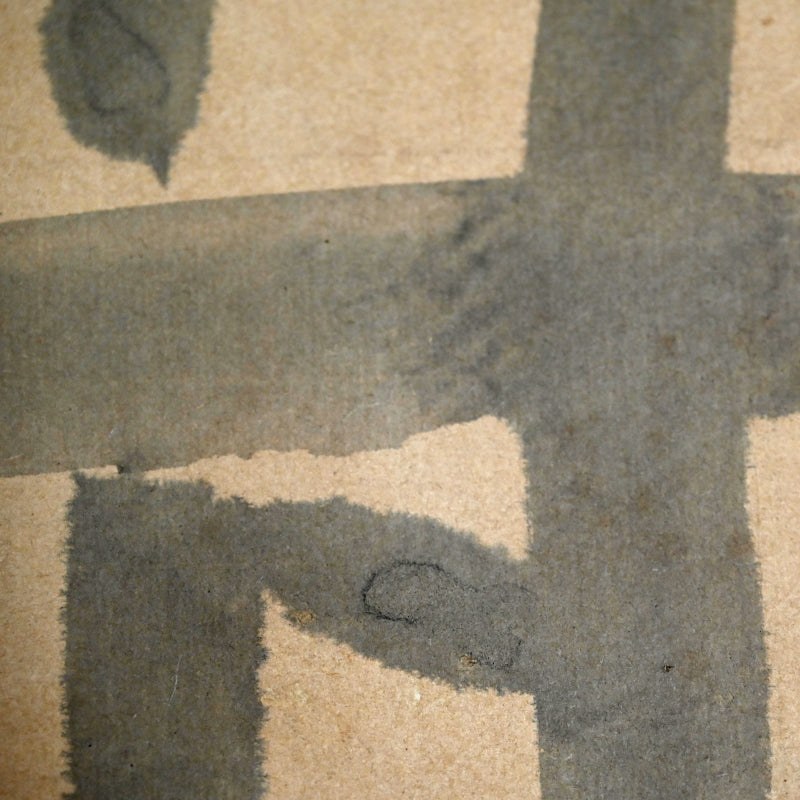

An image of the humble mortar by Hakuin Ekaku in soft ink tones mounted as a scroll suitable for the way of tea or the modesty of monastic life. Hakuin occasionally incorporated household tools like mortars into his Zen paintings and calligraphy, blending folk motifs with spiritual insight. These images often carried humorous or shocking juxtapositions to jolt the viewer out of dualistic thinking. The mortar in Japanese Zen art stands not just as a utilitarian object but as a multivalent symbol—a vessel of transformation, a mirror of emptiness, and a reminder that awakening arises through continuous, grounded, and often humble practice. Just as a mortar grinds coarse matter into fine flour, it symbolizes the relentless effort of zazen (meditation) and koan study—the “grinding down” of delusions, attachments, and ego. The practitioner's mind is refined through rigorous, repetitive discipline. In some Zen parables, the mortar is left empty, emphasizing emptiness, a central tenet of Zen. The object becomes a paradox: empty yet full, still yet active. It reflects the non-dual awareness cultivated through Zen, where distinctions between self and other, tool and task, dissolve. Conversely, “pounding the empty mortar” might be reinterpreted positively—as a way of expressing action beyond gain and loss, a pure manifestation of the Way. Pale ink on paper remounted in dark hand-made momigami reflecting the original mounting and suitable to the humble confines of the monastery or Tea house. It is 56 x 120 cm (22 x 47 inches) and in excellent condition.

Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1768) was one of the most influential figures in the art world of Zen Buddhism. Hakuin Ekaku was born in Hara, Suruga Province (present-day Shizuoka Prefecture). He joined the priesthood at the age of 15, entering Shoinji at the foot of Mt. Fuji, and shortly thereafter moved to Daishoji temple, then Zensoji. However he became disillusioned with the stagnant practices of his time and falling into despair embarked on a rigorous journey of training and self-inquiry leaving the temples to become an itinerant wandering monk. During his travels he came to Zuiunji, where he fell under the influence of the stern scholar Bao. After a profound awakening experience in his early thirties, he emerged as a reformer of the Rinzai Zen school. Eventually he settled at Shoinji, where he would serve as head priest for the rest of hs life, attracting followers from throughout the archipelago. Hakuin revitalized Zen practice by reintroducing strict meditation (zazen), koan study, and direct, often confrontational teaching methods. A gifted teacher and writer, he was also an accomplished painter and calligrapher, using bold brushwork and spontaneous imagery to make Zen accessible beyond the monastic world. His humorous yet piercing visual works—including depictions of Bodhidharma, Zen patriarchs, and folk motifs—communicate profound teachings with immediacy and wit. Rejecting temple-bound seclusion, Hakuin remained rooted in his home village, teaching laypeople and monastics alike. His legacy endures in both the spiritual rigor and expressive freedom he brought to Zen, shaping its trajectory into the modern era.

Share