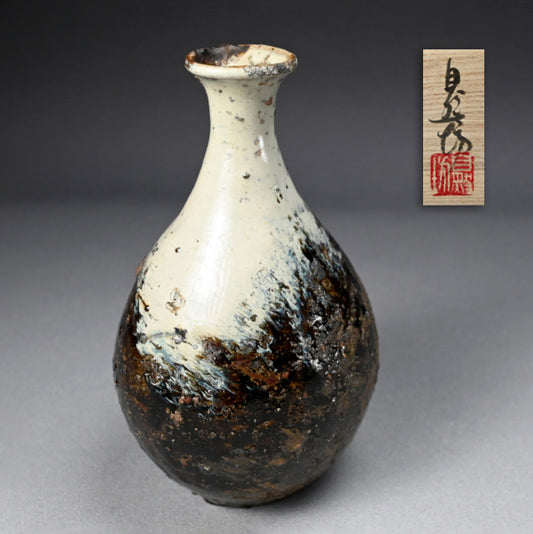

Nakagawa Jinenbo 中川 自然坊

Born in 1953 in the coastal village of Ariura in Saga Prefecture, Nakagawa Jinenbo—given name Kenichi—was raised in hardship by a single mother, his early life marked by poverty and perseverance. After a stint in a pharmaceutical company, his hunger for creative expression and a desire for recognition led him to leave behind the security of salaried work and set his sights on pottery. What began as an ambitious escape soon became a calling. In 1977, he apprenticed under the great Inoue Toya, running 20 kilometers each day to and from the studio. From there, not satisfied with his own skills, he went to Tanaka Sajiro for an additional apprenticeship. By 1982, he had built his own split-bamboo climbing kiln using salvaged materials and earnings from selling vegetables door to door, beginning his journey as an independent potter. A chance encounter with a contemporary artist shifted his path; he came to understand that it is in the fire—yakimono no kokoro—where clay and glaze reveal their true nature. He began working with iron-rich red clay dug from his own land, applying thick white slip with a palm-fiber brush to produce powerful, gestural hake-me ware. His distinctive style caught the eye of Kuroda Sōshin of Shibuya Kuroda Tōen, who would go on to host his first solo exhibition in 1985, marking the beginning of a celebrated and uncompromising career.

By the early 1990s, Nakagawa Jinenbo had firmly established his studio life, building a home-gallery in 1991, a dedicated workshop in 1992, and by 1995, a dormitory to house the steady stream of apprentices who would live and train under his watchful eye. His practice evolved with ambition and risk—in 2000, he turned to the elusive revival of Oku-Korai ware, wrestling with the challenge of reproducing its subtle, loquat-hued glazes. Soon after, he expanded his firing schedule dramatically, conducting over 30 firings a year with his apprentices, relying less on data than on the alchemy of experience and instinct. This period also saw a deepening engagement with tea ceramics: Ido chawan became a new focus, as he began to shift his emphasis from sheer firepower to quiet form, aiming for a sense of dignity and inner strength in each vessel. His work gained national recognition—honored in NHK publications and television programs, and selected for exhibitions such as Contemporary Japanese Ceramics and The Art of Fire. Celebrated in solo shows from Kagoshima to Tokyo, his 20th exhibition at Shibuya Kuroda Tōen in 2006 marked a milestone. Even as illness set in, Jinenbo continued to create and mentor with fierce determination. In 2009, he implemented the previously unthinkable concept of a weekly day off. In 2011, while on oxygen, he produced monumental works for his 30th anniversary exhibition and broke ground on an ambitious new kiln, a hybrid of train and chambered climbing designs. Though completed by year’s end with the help of his disciples, he would not live to see it fired—passing away in December 2011 at the age of 58, leaving behind a legacy of grit, grace, and clay transformed by flame.

-

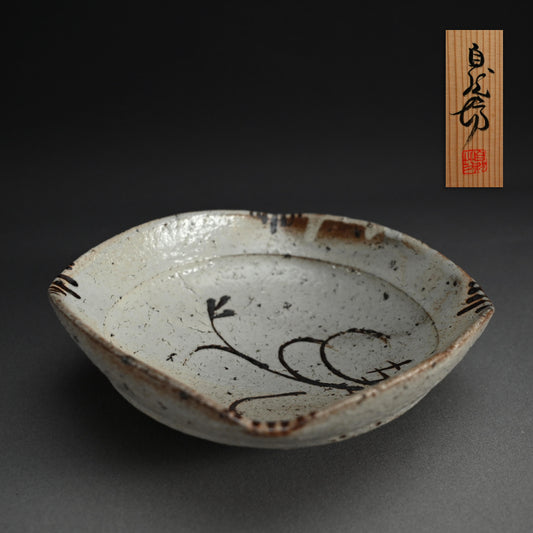

E-Karatsu Tokkuri Sake Flaskー中川 自然坊 “絵唐津徳利”

通常価格 ¥70,500 JPY通常価格 -

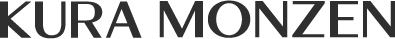

Kohiki Karatsu Kashiki Bowl ー中川 自然坊 “粉引唐津 菓子器”

通常価格 ¥109,700 JPY通常価格 -

Karatsu Bowl ー中川 自然坊 “絵唐津 鉢”

通常価格 ¥94,000 JPY通常価格 -

Chossen Karatsu Vase ー中川 自然坊 “朝鮮唐津花入”

通常価格 ¥155,800 JPY通常価格 -

Karatsu Chawan Tea Bowl ー中川 自然坊 “斑唐津 茶碗”

通常価格 ¥148,800 JPY通常価格 -

Huge Karatsu Bowl ー中川 自然坊 “朝鮮唐津 耳付き波鉢”

通常価格 ¥234,900 JPY通常価格 -

Karatsu Mizusashi ー中川 自然坊 “朝鮮唐津 面取り水指”

通常価格 ¥195,800 JPY通常価格